Fundraising in Morocco

What I learned about attitudes and approaches to fundraising from my two week holiday

👋🏼 Marhaba bikom to Rishtricted Reserves!

I was blessed to visit my family in Marrakech last month. This was my sixth time in Morocco but my first as an official Moroccan citizen! Armed with my Carte Nationale, I could get into many attractions for a reduced price. This was often quite considerable e.g. entry for 10dh, which is less than £1. My dad forgot his card some days and no amount of Darija (Moroccan Arabic) could convince the staff to give him a discounted ticket. I felt smug 😎

This was the first time that my fiancée had visited Morocco and the first time my dad had been back since 2007. So I felt an obligation to be the tour guide for once and take them to all the key tourist attractions around Marrakech that I’ve loved visiting.

As any FUNdraiser would do, I took photos of any examples of fundraising I spotted. Here are three of my observations!

First, a quick overview of the non-profit sector and philanthropy in Morocco.:

Well, it’s not very well regulated, funded or transparent! The bureaucracy I experience in becoming a Moroccan citizen also extends to registering as a ‘public benefit organisation’ or ‘civil society organisation’.

The most popular causes are education, social welfare, female empowerment, the environment and religion. It’s very grassroots and community-driven.

There are a few state-funded Foundations (presided over by the Monarchy) but most grants come from international funding.

Money is only one way Moroccans give. People often prefer to provide in kind gifts like food parcels, clothes, items, sanitary products, medical supplies and basic shelter to those in need via charities.

The vast majority of Moroccans make their biggest gifts as their Zakat. This is an obligation for Muslims to give around 2.5% of their wealth above the Nisab (a minimum amount to live on) to those less fortunate every year. Zakat is second only to prayers in importance within the Five Pillars of Islam.

Pro Bono Economics found that if just the top 1% in the UK donated 1% of their income, it would raise an extra £1.4 billion for charities. Imagine if we could encourage them to give 2.5% of their wealth and how much that would raise!

Despite charity being a big cultural and religious practice in Morocco, 2018 data showed that Morocco was one of the least generous countries in the Middle East and North Africa. There was reduced philanthropic income during Ramadan in 2022 too. Hopefully that recovers post-Covid, with Ramadan currently taking place.

However, we continue to see the generosity and solidarity of Moroccans in their response to the 6.8 magnitude earthquake southwest of Marrakech last year. Some great charities I’ve supported include Amal, High Atlas Foundation and Moroccan Children’s Trust. Check ‘em out!

1. Why do they not ask for donations?

On my two week holiday, I went to 13 cultural and historical landmarks. Most are run as non-profits or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In the UK, almost all of them would ask for donations in some way. However, the only donation box I saw was at the Museum of the Jewish Community of Marrakesh, inside the Al-Azama Synagogue:

I found this strange because cash is king in Morocco. Many places these days accept card payments but a lot of the economy still runs predominantly on cash. If you want to get a taxi or buy almost anything in the souk, you’ll need cash. Venue-based charities in the UK would love to have visitors with as much spare change in their pockets in 2024 as tourists in Morocco.

2. What do they ask for instead of donations?

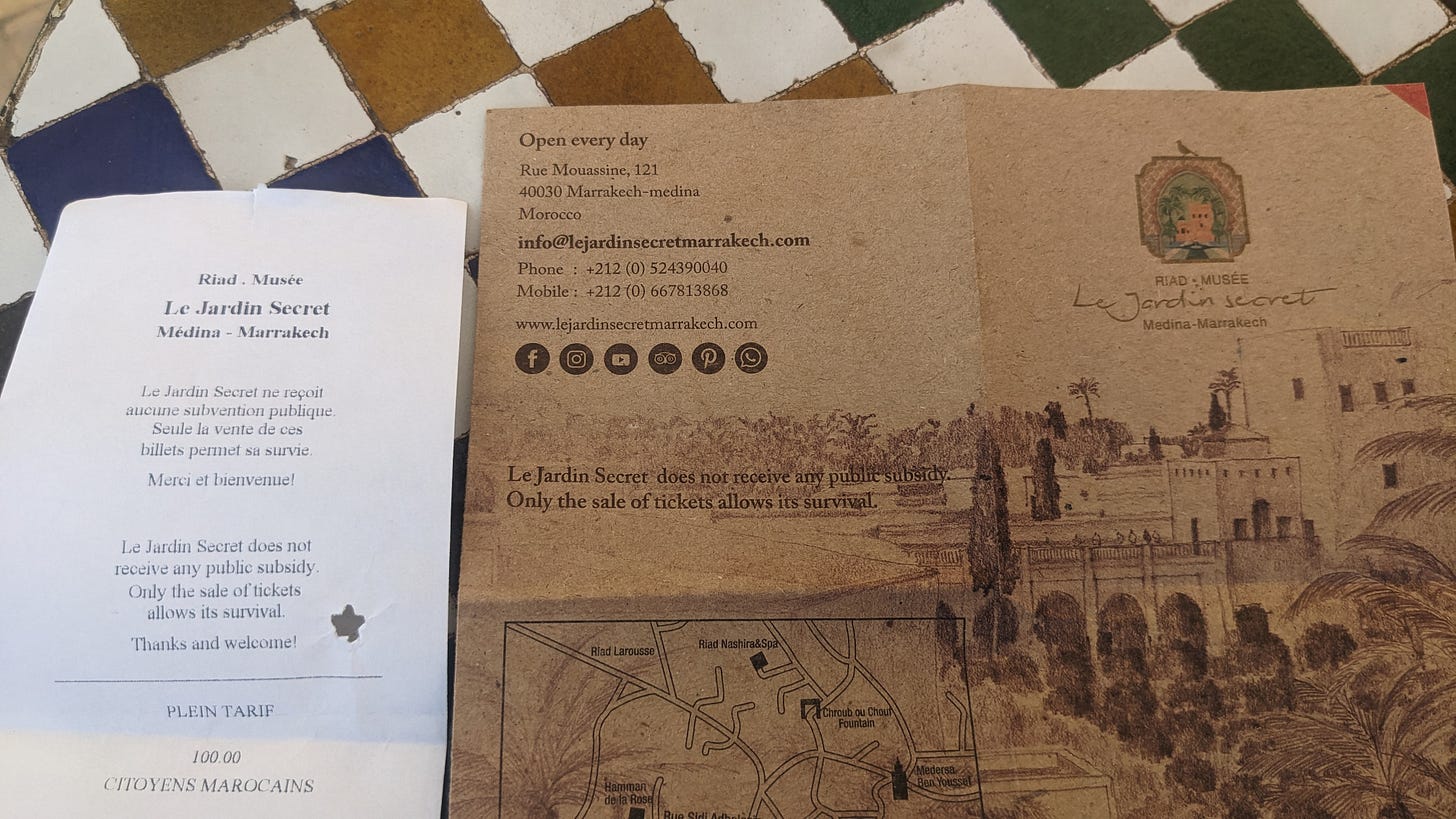

This absence of donation boxes is largely because these institutions choose to sustain themselves through commercial income such as ticket sales, gift shops and cafes. They advertise to the public that their custom is how they can offer support.

This seems like a missed opportunity. Sometimes ticket prices reflect this over-reliance; a full-price ticket for a tourist to Le Jardin Secret is 140dh (about £11), one of the most expensive we bought. However, entry is often comparatively cheap to places. Visitors could afford to donate if they enjoyed their visit and wanted to give more. This limited diversity of income sources restricts the sustainability of these organisations.

3. Why is philanthropy hidden?

Charitable acts are quite secretive and personal in Morocco. There’s a stigma attached to asking for donations and a sense of pride in people and organisations not relying on donations, despite the lack of public subsidy. This is largely due to Islam discouraging public displays of charity.

When an institution does publicly thank its supporters, they’re anonymous.

In fact, a 2015 study found that Moroccans give less often and give a lower figure when their donations are made public. This cultural difference in attitude means that charities in Morocco need to take a contrary approach to fundraising appeals as we would. Moroccans don’t seem to give give for status or ego. Instead it’s altruistic or a moral duty.

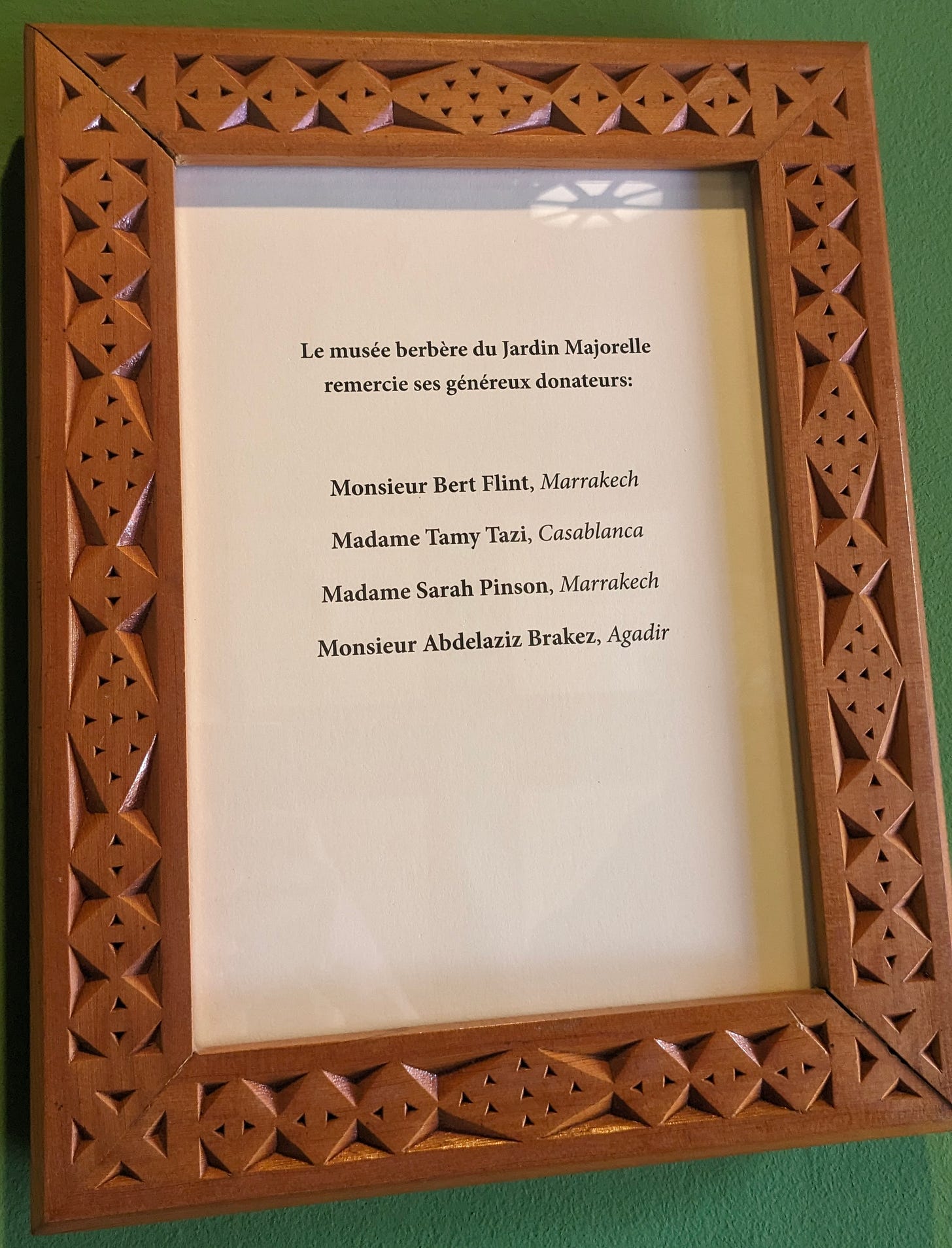

Only one place, Le musée berbère, acknowledged their major donors by name. It’s also a pretty small board in the corner of the entrance that you could easily walk past.

P.S. On the subject of Morocco, I had an essay, Plastic vs. Patience, published in the latest issue of Middleground Magazine. Middleground is an online magazine sharing art, writing, stories and poetry by mixed-race creatives. My essay explores my conflicting feelings of becoming a Moroccan citizen and how it hasn’t made my feel more ‘Moroccan’. I’d love you to give it a read!

A quote I’ve been thinking about while writing this

“There’s no such thing as writer’s block. There’s simply a fear of bad writing. Do enough bad writing and some good writing is bound to show up.”

Have you visited Morocco and noticed any other differences in fundraising? How would you find being a fundraiser in Morocco? Let me know in the comments or reply to this email 👇🏼